The results of research into prehistoric settlement at Lazarides

By Ninetta Kontrarou-Rassia

A hidden side of Aegina hides a thriving Mycenaean settlement, one which is unknown not only to the island’s visitors, but also many Aeginitans. It is on the western side of Aegina where there were, until recently, many small villages, mostly made up of families as one can tell by their names: Benakides, Kanakides, Tzikides – but are now deserted.

One of those villages, with only 10 permanent inhabitants, is Lazarides. And it was just here that in the 14th century BCE the Mycenaeans settled and had an important commercial presence, according to the professor from Athens University, Panagiota Polychronakou-Sgouritsa who has been digging here with her team for the past few years, discovering a vital Mycenaean settlement as well as its cemetery. Mrs Sgouritsa, speaking to the Friends of the National Archaeological Museum, correlated her findings with the recent occupations of the area’s inhabitants and found several similarities.

She also believes that it is possible that this Mycenaean community took over the powerful community of Kolona between the 13th and 14th century BCE – which was the oldest town in the Saronic gulf, whose power seems to decline around that time.

Taking over Kolona

Mrs Sgouritsa notes that up until the 1960s the inhabitants of Lazarides lived off the wheat, olives, vines and vegetables they grew as well as breeding pigs and goats, hunting and fishing. They also sold resin from the pine forests, also a possible Mycenaean activity. The village is located on a mountainous site between Oros and Aphaia and has an unobstructed view of Agia Marina as far as the cape of Ag. Antoni, and the eastern Saronic Gulf even as far as Makroniso and Kea, Modi and Hydra. Footpaths lead down to the harbours at Kilindra and Portes, while roads lead towards the centre and northern parts of the island. Quarries can be found very close by with plentiful supplies of good quality stone. This was the environment where the Mycenaean settlement was created, just 10 kilometres from Kolona which flourished from the 3rd millennium BCE. The Kolona is located in a favourable position on the western and north-western part of the island where its fertile plains are now mostly planted with pistachio trees – and developed contacts with the neighbouring regions and the Aegean islands as early as the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE and by the 2nd millennium BCE with Crete, mainland Greece and the Cyclades.

After the middle of the second millennium BCE findings are also noted on the eastern side of the island such as in the area of the later Temple of Aphaia on the Kilindra coast and at Lazarides.

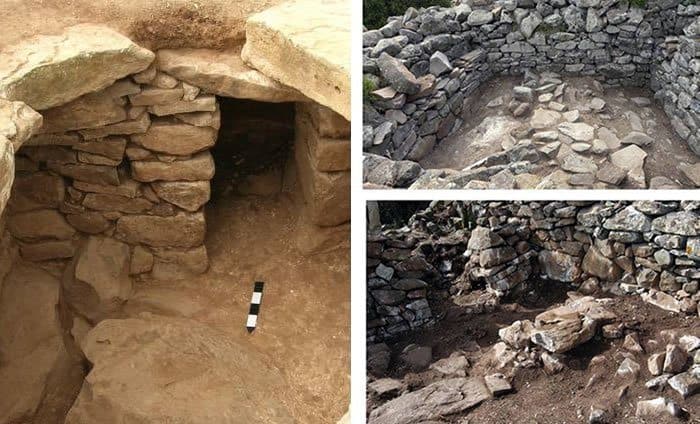

The prehistoric settlement of Lazarides is located at an altitude of 332 metres on a plateau between two hills sloping towards the bay of Kilindra. The coast is steep, the water deep and there are few harbours or anchorages. The site is invisible to those sailing near the coast – so it is well-hidden and safe.

Mrs Sgouritsa, speculates that thriving preshistoric settlement there in the 14th and especially the 13th centuries BCE perhaps replaced the previously powerful Kolona settlement, whose power had declined at that time for unknown reasons.

The excavation is difficult, artifacts are found amongs stones and rocks – it needs hard work and money, of which there is not enough, and that is why only 5% of the settlement has been excavated, according to the archaeologist. The investigation there began in 1979 and 1980 by the Ministry of Culture and has been carried on since 2002 by the University of Athens.

The buildings are stone-built Mycenaean style, with walls reaching to 1.5 metres high and 1 metre thick with small rooms and some large ones as big as 16 square meters. The stone comes from the nearby quarries. What is also of interest is that the prehistoric buildings are similar to the old stone abandoned Aeginitan houses, with the difference that the Mycenaean rooms were larger (7-10 sq m) and resemble the chamber tombs from the ancient cemetery. What is important is that the quality of these structures indicates a level of prosperity.

The Mycenaeans there grew cereals, just like the locals until 1970. In the rooms of the settlement they have found a large number of mills and grinders. Their diet will have been supplemented, says Mr. Sgouritsa, with olives and vines. “Grapes and wine have always existed on the island, once Aegina was renowned in antiquity for these products, which is supported by the islands ancient name of “Οινώνη.” They have also found large jars for oil or wine and a few pits from olives.”

Rich household goods

Possibly the Mycenaeans collected and traded resin products which already in antiquity had many uses, as described by Theophrastus in his treatise on plants. Animal bones have been identified such as sheep and cattle, as well as game (rabbits, deer and wild boar). They ate various seafoods, like today, and made pottery.

The potters made heavy cooking ware, and more rarely unpainted finer ware. Metal objects have also been found such as weapons, tools, jewellery, wires and we know that the raw materials came from Lavrion and Sifno. Among these was a rare lead weight (178 grams), of the same design as those found in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. There were beads from semi-precious stones such as carnelian, cornelian, and rock crystal, as well as seals, which create a rich image of life in this prehistoric settlement – some pieces of wood (from furniture) were found in a semi-basement room with a beautifully preserved copper hair-ornament.

In another room a lead duck was found made from a mold, weighing 20.2 gms. “Such weights are known to come from the eastern Mediterranean of a kind first found in Mesopotamia” the archaeologist says.

Source & picture: www.enet.gr

Translation: Louisa O’Brien